Famous people of Shusha

The people of Shusha made it the pearl of the Caucasus, the cradle of our culture, the mugham-singing heart of Azerbaijan

Famous people of Shusha

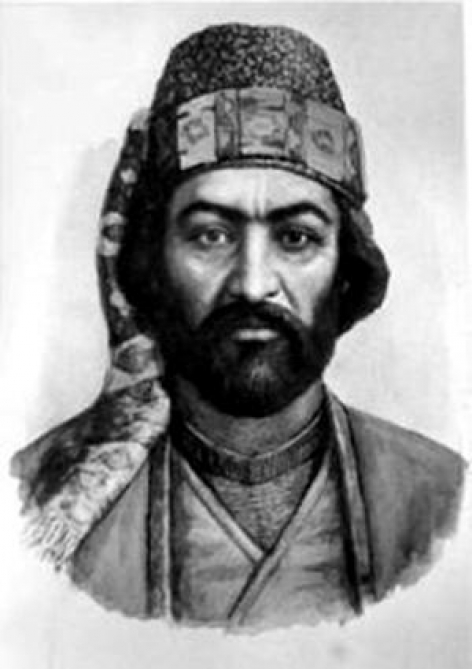

Molla Panah Vagif

Molla Panah Vagif was an 18th-century Azerbaijani poet, the founder of the realism genre in the Azerbaijani poetry and also a prominent statesman and diplomat, vizier – the minister of foreign affairs in the Karabakh khanate.

Vagif was born in 1717 in the village of Salahly, but spent most part of his life in Karabakh. Soon after coming to Shusha, the capital of the Karabakh khanate at the time, Vagif became popular and beloved among the people due to his knowledge and talents. There was even a saying: “Not every literate person can be Vagif”.

As vizier, Vagif did much for the prosperity and political growth of the Karabakh khanate. Also, he played an important role in organizing the defence of Shusha during the incursions of Aga Muhammad shah Qajar of Persia in 1795 and 1797.

The historian Mirza Adigozal bey records the following possibly apocryphal tale: during the 1795 siege of Shusha, which resisted stubbornly despite the overwhelming numbers of Aga Muhammad’s army, the shah had the following couplet by Urfi, the Persian-Indian poet, attached to an arrow and shot behind the walls of the city:

زمنجنیق فلک سنگ فتنه می بارد

تو ابلهانه گریزی به آبگینه حصار؟

Lunatic! A hail of stones descend from the Catapult of heavens,

while you await wonders in walls of glass?

The shah was playing on the meaning of Shusha: “glass” in Persian (and Azerbaijani language). When the message was delivered to Ibrahim Khalil khan, the ruler of Shusha, he called upon Vagif, his vizier, who immediately wrote the following response on the reverse of the message:

گرنگهدار من آنست که من می دانم

شیشه را در بغل سنگ نگه میدارد

If my protector is the one that I know,

[he] would protect the glass alongside the most solid stone.

Receiving the letter with this poem, shah Aga-Muhhamed went into a rage and renewed the cannon attack on Shusha. However, after 33 days, the shah lifted the siege and headed to Georgia.

Shah Qajar invaded Karabakh a second time in 1797, after the Russian armies that briefly occupied the Caucasus were withdrawn on the death of Catherine II. This time, Karabakh was undergoing a drought and was incapable of resisting. Ibrahim Khalil khan escaped Shusha and the city fell quickly. Vagif was imprisoned and awaited death the following morning but was saved when the shah was assassinated that very night under mysterious circumstances.

The reprieve did not last long. The nephew of Ibrahim Khalil khan, Muhammed bey Javanshir, came to power after the Persian army returned to Iran. Seeing in Vagif a loyal follower of his uncle, he had Vagif and his son executed. At the time of his death, his house was plundered and many of his verses were lost.

Vagif’s remains were kept in Shusha, where a mausoleum in his name was built during the Soviet era in the 1970s. This mausoleum was destroyed in 1992 during the First Karabakh War. However with the liberation of Shusha by the Glorious Army of Azerbaijan at the result of the Second Karabakh War the restoration of the mausoleum has started upon the instruction of President Ilham Aliyev and it is expected that the restoration work will be completed summer of 2021.

Despite the circumstances of his death, Vagif’s poetry has persevered. His verses were collected for the first time in 1856 and published by Mirza Yousif Nersesov. Soon afterwards, his verses were published by Adolf Berge in Leipzig in 1867 with the assistance of Mirza Fatali Akhundov, a prominent 19th-century Azeri playwright.

Vagif’s works herald a new era in Azeri poetry, treating more mundane feelings and desires rather than the abstract and religious themes prevalent in the Sufi-leaning poetry of the time. This was the main characteristic that distinguished Vagif from his predecessors and made him the founder of the realism genre in Azeri poetry.

The language of Vagif’s poems was qualitatively innovative as well: vivid, simple, and closely approaching the Azeri vernacular. Vagif’s poems have had a great influence on Azeri folklore and many of them are repeatedly used in the folk music of ashigs (wandering minstrels).